Lethal Theory explores Israeli Defence Force (IDF) tactics in Nablus, Palestine, April 2002. Palestinian resistance had barricaded all entrances to the old city and mined the roads, so the IDF gained access by "walking through walls" - that is, blasting holes in them and moving through the city using complex routes through Palestinians' homes, making the city not merely the site but the medium for urban warfare. This "microtactic" was conceived by the IDF's Operational Theory Research Institute in explicitly deleuzeandguattarian terms, such that the IDF would only defeat their enemy's classical, striated conception of space (ordered around roads, barricades, walls) through making the city 'smooth', borderless for their incursion.

We walked into the block of flats through an open door. Up the stairs. A few flats were still inhabited, more sealed tight with heavy metal doors and window coverings. A handful though were open - completely open, without any doors and windows, inhabited by only fresh air and pigeons, topographically - as we had passed through no boundaries or barriers, just a series of passageways - still outside. (This, when vigilante security and then the police showed up, was our defence.)

The flats were almost empty. An old exercise book dated 2002, a benefits letter from 2003. A coathanger, a piece of string with pegs still attached.

The space felt wrong, uncanny. A bath shouldn't be on top of a bedstead. Wallpaper in the next room flapped in the wind, and pigeons nested in the ceiling cavities. Very literally unheimlich. The gaps where electricity cables and pipes had been ripped out to make the place uninhabitable. Homes are bodies to me. I didn't like that.

That's why the doors and windows had been removed too, we realised - to keep squatters out. The stairs had gone too, but we climbed.

I don't want to draw a parallel with what Weizman wrote; in fact, I'm trying to resist it. This isn't war, it's just housing redevelopment. The meaning isn't the same, the meaning isn't the same at all. I don't think the two situations are commensurable.

And yet... Why is the visual symbolism so similar? How far do these similarities continue through the very structure of these spaces? Points of contact:

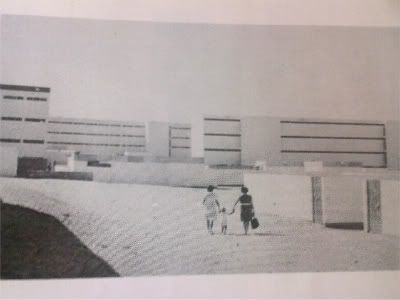

1. You've got the last few people living in the block and refusing to leave their homes despite the fact these are being made a wasteland. The effect on the outside of the building is violent, like missing teeth. It's a tactic of making a ruin in order to force people out (residents) and to make it impossible for them to stay securely (squatters).

2. This destruction of the "syntax of the city, ...the external doors, internal stairwells, and windows that constitute the order of buildings, this destruction that redefines inside and outside and refuses "to submit to the authority of conventional spatial boundaries and logic". (Weizman 2002: 53) This turning inside out seems a radical thing for power to do: "This was your home? That means nothing." Radical to do this topologically - the idea of home (in the Anglo-West) is predicated upon making a distinction between inside/outside in order to define private/public. It is a matter of borders and boundaries. The removal of windows and doors (the housing block) or walls (Nablus) makes these spaces merely a complex folding of outside space.

3. The intention of the building owners apparently "not to capture and hold ground" (2002: 56) but rather make it so permeable that no-one else can hold that space and turn it to their own uses or resist the development. These spaces windowless and breached do not even require IDF sensing technologies to "see through walls" - illicit occupants are visible from the street; these once-homes, formerly metaphorically Englishman castles, are now panoptical.

4. The developers are locking up some flats (thick green submarine doors, grey window sheaths) and opening out others - yet apparently for the same ends. (Why some flats get one treatment and others another, I'm unsure - but curious.) Similarly Weizman notes in an aside that, in their knocking-through, the IDF would still lock up Palestinian families in a single room and leave them there for days.

5. Difference: the IDF tactic is about letting Israeli soldiers pass through; the UK developer's tactic is about preventing squatters from staying. Nonetheless in both cases bulidings are not just the sites of these interventions but the very mediums, and the tactic is one of removal rather than addition - something counter to typical security thinking oriented around the encrustation of gates, locks, checkpoints, added barriers.

6. Power is enacted not just on space but on movement: enabling movement for the IDF; enforcing it for potential squatters to the housing block, for whom it is made impossible to stay.

Thus in two quite separate contexts of power acting on people's homes there is a strangely similar visual lanaguage (holes in walls), and three critical strategic similarities: building as medium; a tactic of removal; and power over not only space but movement.

What does these similarities mean? That is my burning question, and one I still can't quite answer for myself. Still, the quotation below is food for thought:

...address not only the materiality of the wall, but its very essence. Activities whose operational means effect the 'un-walling of the wall' thus destabilise not only the legal and social order, but democracy itself. With the wall no longer physically or conceptually sacred or legally impenetrable, the functional spatial syntax that it created - the separation between inside and outside, private and public, collapses. The very order of the city relies on the fantasy of a wall as stable, solid, and fixed.

(Weizman 2002: 75)

While quite arguably true for Nablus it's clearly too much for North London; nonetheless the point about spatial syntax holds true, and I wonder if these strange empty flats do something to the order of the city too. It brings to mind the 'broken windows' theory of crime writ large - if supposedly supportive council housing has such gaping wounds facing the street, how exactly can we expect some Manor House 13-year-old to believe that the destruction of property is a crime?

1. Credit to Adrian @cunabula for the topology insight.

2. Next reading group Wednesday 9th June, northeast London somewhere. If you're reading this you're welcome - drop me a line.